OTHER-worldliness marching against the arrows of TIME.

The more you try to erase me, there more that I appear.

Who Made Daveyton

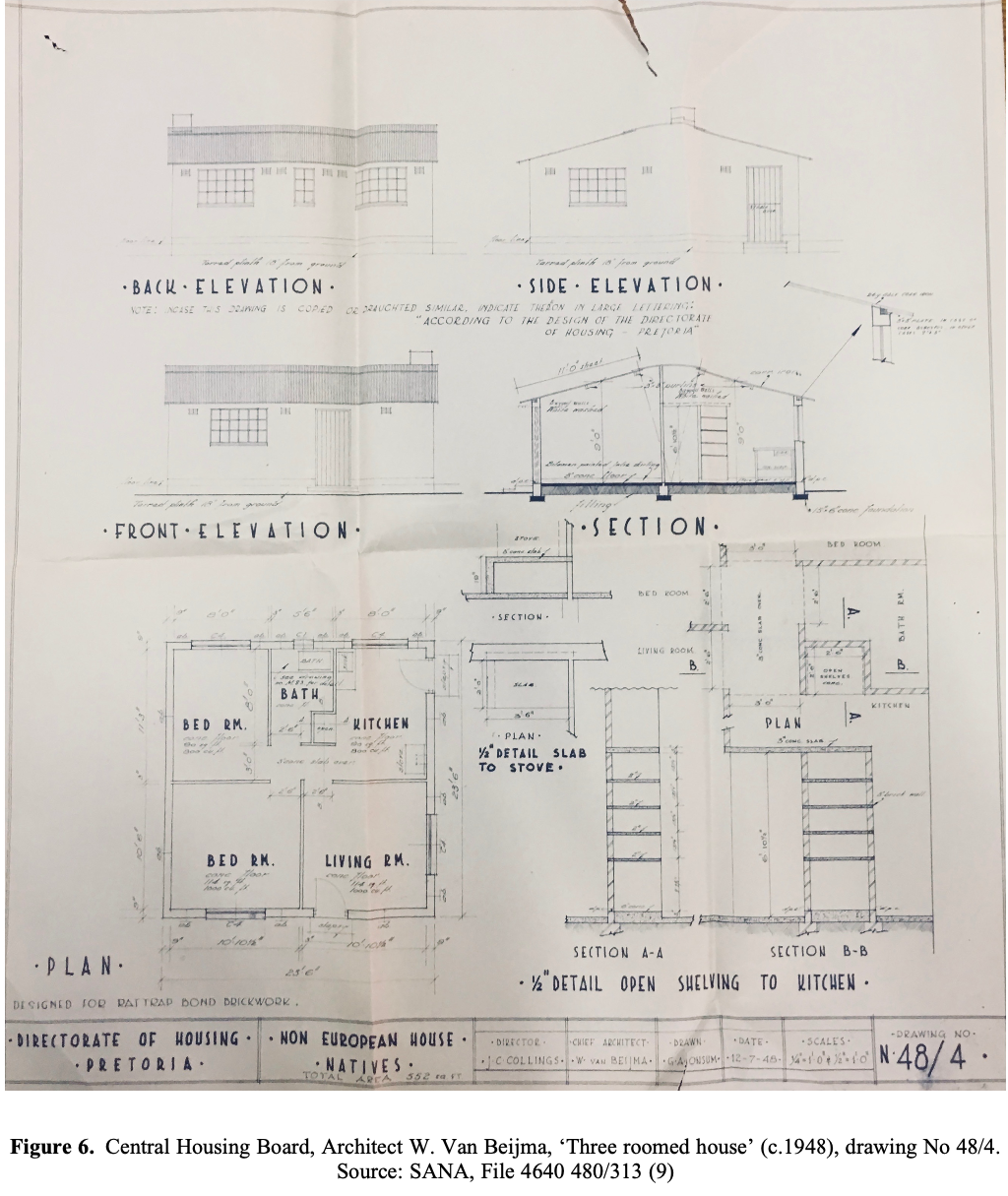

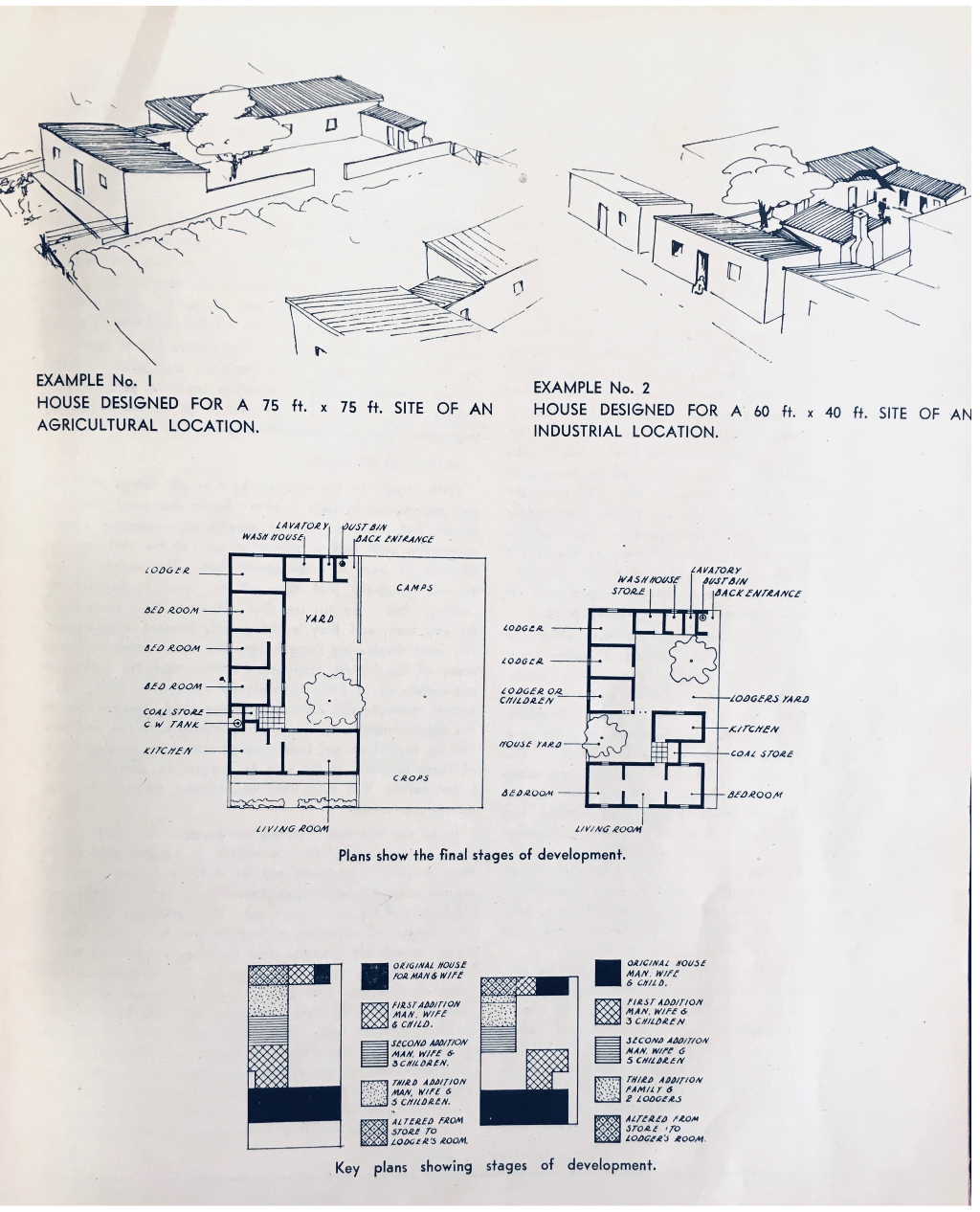

Daveyton Blueprints.

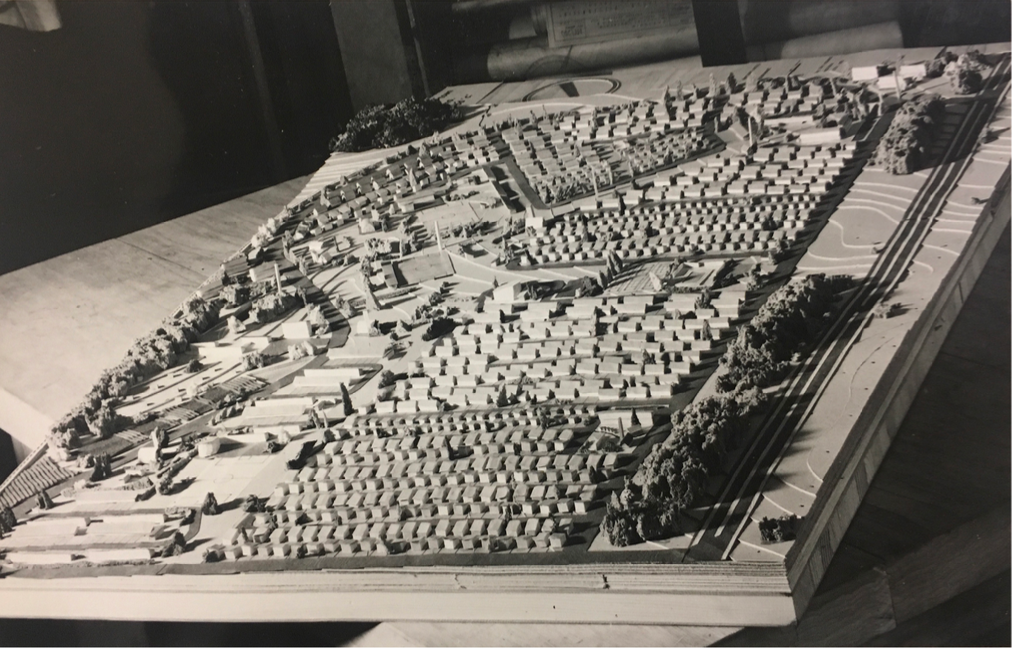

Townships like Daveyton were never accidents. They were laboratories for the national project: to “civilise” the majority while constructing an identity that served colonial european economic and hegemonic interests. The logic of apartheid shaped them. Engineered with precision to contain, monitor, and control Black life.

Benoni Mayor’s credit list

A list of Benoni Mayors since the early 1900s

Daveyton is the site for a new curriculum.

The New Patterns: Style of Sounds Workshop was both a learning programme and a pedagogical exercise. The New Patterns artistic programme aims to decentre fashion knowledge production through ways of teaching and learning and to welcome new, decolonial fashion knowledges in terms of both content and its frameworks.

Despite rich historical evidence in buildings, stories and memories, much of Daveyton’s past is dispersed as overlooked fragments of history. Since 2021, Erica de Greef has worked closely with Daveyton-based researcher Bongani Tau, founder of Abengoni and Daveyton1520, exploring ways in which fashion can be used to address historical erasure. Together, they asked what it could mean to position Daveyton as the site for a new curriculum project, and how thinking from Daveyton could contribute towards decolonising pedagogical practices in design and related disciplines. And so, in January 2024 the New Patterns: Style of Sounds Workshop took place in Daveyton on the East Rand of Johannesburg. The New Patterns workshop, supported by the National Arts Council, was presented by AFRI and coordinated by Scott Williams.

It was hosted by the Rhoo Hlatshwayo Art Centre and Brima Café, both well-known establishments in Daveyton, from 17-19 January 2024. Drawing on the power of fashion as a route to rewrite histories, the workshop invited fashion thinkers, thrifters, digital photographers, musicians, stylists, educators and entrepreneurs to tap into the collective memories of the township in order to redress historical absences. Fashion played a significant role in the lives of its residents and acts as a powerful archive and a placemaking device. Over three days, they mapped out various fashion histories drawing on photographic records, material biographies, upcycling practices and oral knowledges. The workshop culminated in a recreated jazz event, and the production of a series of digital photographs and short film.

❋

Reflections

When Township Image-Making Outruns Visual Theory: Daveyton as a Theoretical Site for Fashion Studies

by Dirk Reynders

This article examines township image-making in Daveyton (Ekurhuleni, Gauteng) to argue that several widely used analytic vocabularies in visual theory and fashion studies- particularly realism, masculinity, and formalism-do not always travel well into contexts shaped by apartheid spatial governance, uneven infrastructures, and informal publics (Nieftagodien, 2013). Rather than treating Daveyton as a bounded “case study” that illustrates concepts formed elsewhere, I approach it as a theoretical site that exposes the limits of inherited repertoires and makes conceptual recalibration unavoidable within fashion studies (Jansen, 2020; Niessen, 2020).

I write explicitly as a white European researcher working across a Global South context. Positionality is treated here not as a credential but as a constraint on what can responsibly be claimed, named, or generalized. In line with methodological critiques, positionality is framed as a practice of epistemic accountability that must be tied to changes in method, citation, and authority rather than functioning as a ritual of legitimacy (Eriksen, 2022; Gani & Khan, 2024; Zembylas, 2025).

Building on scholarship on Daveyton’s apartheid-era governance (Nieftagodien, 2013), contemporary township creativity and informality (Booyens, 2025), and township sartorial performance and moral economies (Mnisi & Ngcongo, 2023), the article reframes township image-making as infrastructural practice: a way of negotiating dignity, legibility, and status where institutions associated with “the fashion system” may be absent, hostile, or unreliable. To support this argument, I introduce three working terms-situated realism, vernacular formalism, and infrastructural visibility-offered as unstable heuristics rather than definitive labels. The term vernacular formalism is handled with particular caution because “vernacular” carries a colonial afterlife and can function as a classificatory mechanism that domesticates practices that should instead reorganize theory.

Keywords: township; Daveyton; fashion studies; visual theory; decolonial fashion discourse; masculinity; realism; formalism; visibility; Izikhothane.

1. Introduction: Why Fashion Theory Needs Township Image-Making

Fashion theory has long insisted that dress is never merely clothing: it is a technology of body-making, social ordering, and cultural power. Yet even within critical fashion studies-and even amid sustained challenges to Eurocentrism-there remains a recurring asymmetry in how theory is imagined to move. Too often, concepts are stabilized in Global North institutional settings (fashion schools, museums, editorial cultures, “fashion system” infrastructures) and then applied elsewhere, while Global South contexts are recruited as evidence that enriches analysis without reorganizing the conceptual vocabulary doing the analysis.

The “Decoloniality and Fashion” debates made this asymmetry harder to ignore by centering coloniality as constitutive rather than incidental to fashion’s modern operations. Jansen’s (2020) framing of decolonial fashion discourse challenges fashion’s false claim to universality and calls for epistemic plurality beyond modernity’s narrative. Niessen (2020) argues that sustainability frameworks often reproduce colonial hierarchies by treating many global clothing traditions as “non-fashion,” effectively relegating them to a sacrifice zone. De Greef (2020) demonstrates how curating can work as decolonial practice by tracing political histories in the “seams” of a fashion object, while Slade (2020) argues that “luxury” itself can be read through colonial modernity. Cheang and Suterwalla (2020) extend these stakes to pedagogy, insisting that decolonizing fashion education involves transformation, emotion, and positionality rather than a simple diversification of syllabi. Cheang, Rabine, and Sandhu (2022) further stress decolonizing fashion studies as an ongoing, non-linear process rather than a completed achievement.

This article aligns with those interventions but argues that township image-making presses fashion studies in a specific direction: it asks what happens when fashion knowledge is produced and judged outside the institutional architectures the discipline often presumes-even when critiquing them. If “the fashion system” remains a powerful analytic object, township image-making suggests that other systems of fashion valuation operate through peer publics, informal infrastructures, and platform-based circulation. These publics can be volatile and intensely moralized. They can also be sophisticated, generating repertoires of style, evaluation, and embodiment that do not wait for institutional authorization.

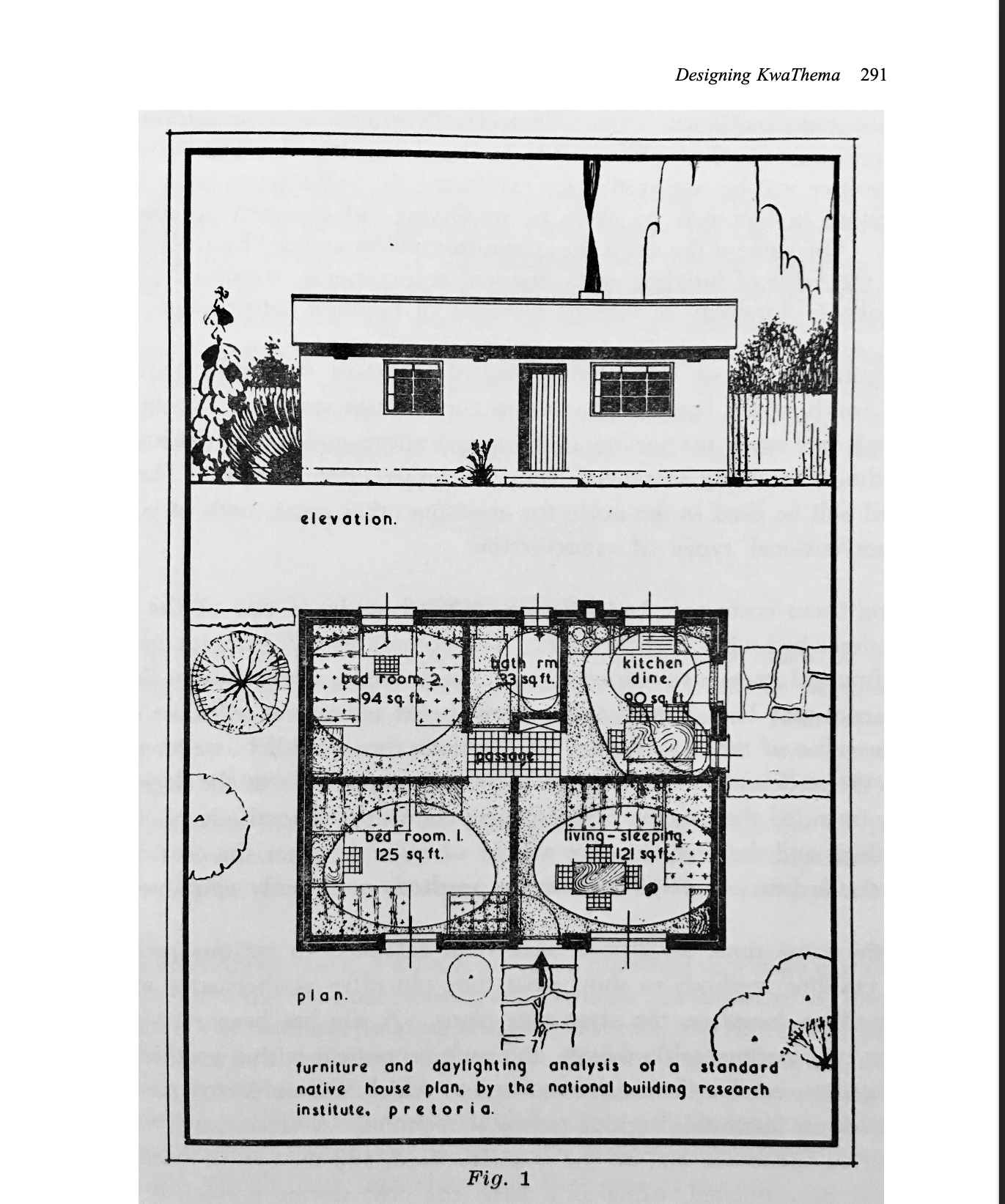

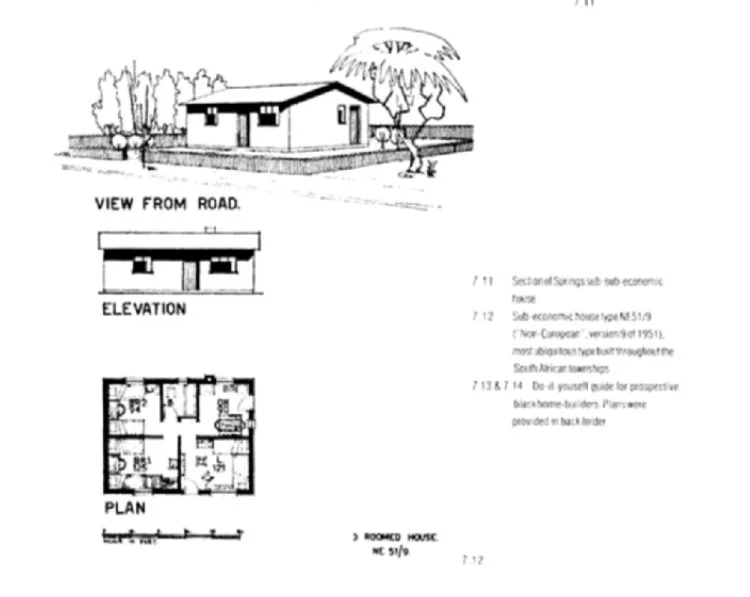

Daveyton is approached here as a site where these issues become conceptually legible. Its apartheid-era history matters, not as a backdrop to be summarized and then set aside, but because the governance of space is also the governance of visibility. Nieftagodien (2013) describes Daveyton in the 1960s as a “modern model township,” tracing how apartheid authority eroded “official” local politics and attempted to manage African urban presence. If the conditions under which Black life could appear in urban space were historically engineered, then the conditions of appearing-of being seen, styled, recognized, and circulated-remain politically charged.

The central claim of this article is modest but firm: township image-making in and around Daveyton exposes recurring limits in Global North–dominant visual theory and in fashion studies when realism, masculinity, and formalism are treated as stable categories. These categories do not simply “fit” or “not fit.” Rather, township image-making reveals how their institutional assumptions often remain unspoken-assumptions about the availability of archives, the security of publicness, the desirability of visibility, and the authority of institutions to validate aesthetic value.

Because the impulse to invent new terms can reproduce the very asymmetry the article critiques, the working terms introduced below are framed as provisional and unstable. Their purpose is not to “name” township life, but to keep pressure on fashion theory’s inherited habits and to make conceptual limits discussable.

3. Daveyton, Visibility, and the Non-Innocence of Publicness

Daveyton’s apartheid-era history foregrounds a question fashion studies and visual theory sometimes treat too quickly: what is the public, and who is allowed to appear within it? Nieftagodien’s (2013) account of Daveyton as a “modern model township” in the 1960s emphasizes how apartheid governance targeted the limited rights enjoyed by Africans in urban areas and reshaped local political participation. The township was not merely a neighborhood; it was part of a system of spatial control, labor management, and racialized governance.

Under such conditions, visibility is never simply an aesthetic matter. It becomes entangled with surveillance, regulation, and the moral narration of Black life. This historical lens matters for contemporary township image-making because it helps explain why appearing can be both necessary and risky. In much liberal discourse, visibility is assumed to be an uncomplicated good: to be visible is to be recognized. Yet in township settings, visibility can bring recognition and humiliation, protection and exposure, mobility and policing.

Fashion studies has strong tools for reading dress as a site of politics and embodiment. Township image-making asks fashion studies to extend those tools into infrastructural questions: what makes appearance possible, who can circulate images safely, who becomes the object of moral scrutiny, and how value is produced when institutions are absent or unreliable.

4. When Traveling Concepts Break Down

This section takes three pressure points-realism, masculinity, formalism-and asks how township image-making complicates each as a traveling concept. The goal is not to discard these concepts. It is to make their hidden institutional assumptions visible and to propose working terms that may better track the infrastructural realities of township image-making as fashion practice.

4.1 Realism: from depiction to claim

In Global North traditions of visual theory, realism is often anchored in descriptive fidelity: the realist image is “true” insofar as it accurately depicts social conditions. In contexts of inequality, realism frequently becomes an ethical demand: show poverty as it is; show violence without embellishment; show suffering without aestheticization.

Township image-making complicates this demand because it is often evaluated through a narrow expectation of what township “reality” is allowed to look like. When township subjects are required to be “real,” they are often required to be legible through deprivation. Glamour, spectacle, and excess are then treated as falsehood or denial, as if stylization cannot itself be a truth practice.

Scholarship on township sartorial performance makes this limitation explicit. Mnisi and Ngcongo (2023), in their analysis of African masculine sartorial subcultures including Izikhothane/Via Daveytons, argue that conspicuous consumption and sartorial excess can function as rehumanization in lives “bereft of dignity.” Their argument does not claim that these practices are uncomplicatedly emancipatory; rather, it insists that they cannot be reduced to irrational consumerism or moral failure. Stylization is not simply aesthetic. It is often a social technique for negotiating worth and recognition.

Coulter, Martin, and van der Westhuizen (2025) offer a related lens through “tournaments of destruction,” defined as staged and ritualized social performances involving competitive rivalry in which consumers destroy valued objects before a focused gathering. Their framework is not identical to township sartorial subcultures, and it should not be collapsed into them. Yet it helps fashion studies articulate a broader point: in reputational economies, material value may be converted into symbolic and social value through performance, even through acts that appear materially irrational when judged by norms of preservation. In contexts where conventional routes to status are blocked or unstable, visibility itself can operate like a scarce resource-and stylization becomes a strategy for generating it.

These literatures suggest that realism-as-depiction is too narrow for township image-making. The image often functions less as documentation of socioeconomic conditions than as an assertion of personhood within them. Truth, in such contexts, includes the struggle over the terms on which one is allowed to be seen.

Situated realism is proposed here as a working term for this shift. Situated realism treats realism as a claim rather than a depiction: an insistence on socially actionable truth about the self-dignity, worth, legibility-under constraint. The claim may be made through spectacle, excess, or stylization not because reality is irrelevant but because reality includes the politics of who is granted full personhood and on what visual terms.

4.2 Masculinity: from representational theme to visibility regime

Masculinity is often approached in visual and media studies as a representational object: a set of scripts and stereotypes that images reproduce or contest. Township image-making suggests that masculinity also operates as a visibility regime-an ensemble of public techniques for managing recognition, rivalry, vulnerability, and respect. In other words, masculinity is not only what images show; it is how one navigates the risks and rewards of being seen.

Ratele’s (2021) “invitation to decoloniality” in work on (African) men and masculinities is crucial for understanding why imported masculinity frameworks can misfire. Ratele asks what “place/s” are available to men once regarded as property under colonial regimes and how masculinities studies can reckon with coloniality as constitutive rather than external to African masculinities.

Township image-making gives this question a fashion-studies texture: masculinity is enacted through dress, stance, gesture, and peer-adjudicated performance in spaces where histories of racialized governance and contemporary economic precarity shape what respectability, strength, and dignity can look like. Mnisi and Ngcongo (2023) show how township masculine sartorial practices are often moralized from the outside as deviance or irresponsibility, yet may operate internally as attempts at rehumanization. Coulter et al. (2025) help illuminate how competitive spectacle can regulate belonging and status through public performance.

Treating masculinity as a visibility regime has implications for fashion studies. It shifts analysis away from masculinity as a stable identity category and toward masculinity as technique: practices of appearing that manage risk and recognition in specific infrastructures of publicness. This approach does not deny that masculinity can reproduce domination; it insists that in township contexts masculinity is also shaped by histories of dehumanization and by the practical demands of being legible in spaces where misrecognition can be costly.

4.3 Formalism: from aesthetic autonomy to infrastructural craft

Formalism in art history is often associated with the analysis of form as form, sometimes sheltered by the ideal of aesthetic autonomy. Even when fashion studies critiques strict autonomy, it can retain a habit of treating form as if it were a stable object ready for close reading.

Township image-making complicates this because formal decisions are frequently inseparable from informal infrastructures: access to goods, borrowing networks, informal retail circuits, spatial constraints, platform affordances, and peer publics that evaluate style without institutional mediation.

Booyens (2025) provides a useful framing: township creativity emerges in spaces characterized by informality and marginalization, and scholarship can be silent about these spaces because they do not align with dominant urban creativity narratives. Translating that insight into fashion theory suggests that formal intelligence may be abundant where institutional recognition is absent. “Good form” may be produced through different criteria: not only artistic innovation or runway coherence but also legibility, reputational stakes, and the capacity to circulate in local and platform publics.

To name this without romanticizing it as pure resistance, I propose vernacular formalism as a working term-while simultaneously treating it as a conceptual risk.

Case 1 — Daveyton as a living curriculum: New Patterns: Style of Sounds (Jan 17–19, 2024)

A strong way to ground your argument is to treat New Patterns: Style of Sounds not as an “example from the township,” but as an epistemic intervention: a deliberate attempt to produce fashion knowledge from Daveyton, through methods that merge archive, memory, making, and performance. Hosted in Daveyton (Rhoo Hlatshwayo Art Centre and Brima Café), the workshop explicitly frames fashion as a route to rewrite histories and address historical erasure, using a mixed ecology of participants (researchers, thrifters, photographers, musicians, stylists, educators, entrepreneurs) and mixed materials (photographic records, material biographies, upcycling practices, oral knowledges). Its outputs are also explicitly archival: “6 new historical portraits,” “(k)new visual archives,” and a “short shareable film,” alongside community formation and future fashion-led research (African Fashion Research Institute [AFRI], n.d.).

What matters here is that the workshop operationalizes the archive as practice rather than container. It echoes the idea that archives are not neutral storehouses but institutional and infrastructural arrangements of power—while also showing how counter-archives can be made through lived collaboration, not only through official repositories (Mbembe, 2002). Instead of extracting “culture” for external legibility, the workshop’s method produces an archive through relational labor: mapping local histories via clothing and styling as embodied knowledge, then re-staging a jazz event to materialize memory as a social form. In this sense, fashion becomes both method and medium: a way of thinking through place, time, and subjectivity, and a way of building new public memory objects.

Analytically, this case lets you demonstrate three key claims:

1. From object to method: Daveyton is not positioned as content to be represented, but as a site where theory is generated. The “data” are not simply images; they are the workshop’s procedures for making images meaningful: selection, narration, styling, and re-performance.

2. From archive to repertoire (without romanticizing): The workshop moves between recorded artifacts (portraits/film) and embodied transmission (recreated jazz event; oral histories). This aligns with the archive/repertoire distinction while refusing to frame embodied knowledge as secondary or “informal” (Taylor, 2003). Importantly, the point is not to celebrate ephemerality, but to show how memory work is organized, shared, and authored.

3. Anti-domestication through specificity: The workshop’s strength is its specificity: named hosts, dates, sites, contributors, and concrete outputs (AFRI, n.d.). This resists “soft domestication” because it refuses the vague language that often turns Global South creativity into a floating aesthetic category.

Case 2 — Digital witnessing as counter-archiving: @Daveyton1520 / Abengoni as a “route to remember”

Your second case can foreground platformed archiving as a mode of knowledge production-where fashion imagery becomes a discursive tool to interrupt colonial borders in education and historiography. In Digital Fashion: Theory, Practice, Implications, Erica de Greef (with King Debs, Siviwe James, Lesiba Mabitsela, and Sihle Sogaula) describes Bongani Tau’s Instagram platform @Daveyton1520 as a “discursive portal” that makes visible obscured histories and everyday resilience in marginalized township communities. Crucially, the platform is framed not as social media content but as a metanarrative with knowledge-making and place-making possibilities (de Greef et al., 2024).

2.1. Fashion-as-thinking, not fashion-as-spectacle

The chapter explicitly frames the platform as more than visual display: Tau uses it as a “route to remember,” positioning posts as critical archives that document “a black politics of being.” In this framing, fashion is not reduced to style; it becomes a method for reading the social world-linking embodiment, environment, and memory (“Fashion-as-thinking becomes both a lens and a method… spanning a politics of memory and a politics of becoming”) (de Greef et al., 2024).

This supports your push against Eurocentric vocabularies that treat Global South fashion as either “vernacular charm” or aspirational imitation. Here, fashion is a theoretical instrument: a way to produce concepts about borders, belonging, and endurance.

2.2. Counter-canon formation through access and circulation

The digital archive functions by collapsing gatekeeping structures-who gets to speak, who gets seen, and whose histories are teachable. The chapter’s broader section argues that digital archives can disrupt knowledge gatekeeping by creating flexible spaces of collation, curation, exchange, and access (de Greef et al., 2024).

2.3. Strengthening the case with “ground truth” beyond the platform

To avoid the common trap of treating the digital feed as a self-contained universe, you can anchor the platform’s memory work in adjacent local historiographic practices. For example, local educators and researchers in Daveyton have also produced community-based historical narration through long-form research projects such as the book Amaqhawe ase Daveyton-built through years of research and oriented toward teaching local history to younger generations (Komape, 2023).

You don’t need to claim equivalence; instead, you can show an ecosystem of memory practices (platform + book + tours + workshops). That ecosystem is precisely what makes Daveyton legible as a theoretical site rather than a cultural object.

2. Positionality and Epistemic Limits: From Declaration to Method

I write as a white European researcher engaging a Global South site. I name this directly because it shapes not only ethics but epistemology: it affects what I am trained to treat as “theory,” what kinds of evidence feel familiar, and how easily township practices can be converted into academic value within Euro-American publication economies. The history of representing township life-across documentary traditions, news discourse, cultural tourism, and critical scholarship-includes long-standing patterns of extraction and moralization. Being conscious of the forces that shape my work does not free my work from those forces.

For that reason, positionality is treated here as a methodological limit rather than a self-sufficient disclaimer. Gani and Khan (2024) argue that positionality statements can function as rituals of legitimacy-appearing reflexive while leaving intact the colonial distribution of interpretive authority. Zembylas (2025) cautions that positionality statements can stabilize identity categories and re-inscribe hierarchy unless they are linked to practices of solidarity and material transformation. Eriksen’s (2022) account of the “reflexive wrestles” of whiteness underscores that the problem is not solved by declaration; it requires ongoing attention to how whiteness can re-enter through comfort, conceptual certainty, and the centering of one’s own explanatory voice.

2.1 The limits of the archive

A recurring methodological problem in fashion studies is that archives-and the concepts built around them-are treated as sufficient evidence of fashion’s operations. Township image-making makes this confidence harder to sustain. In many township contexts, image-making circulates through informal infrastructures and ephemeral publics; it may not sediment into the kinds of archives that academic fashion studies is trained to privilege. This does not mean that township practice lacks history; it means history may be held and transmitted differently-through people, stories, rivalries, networks, and the embodied repetition of style.

Within the limits of an article-length intervention, the response cannot be to “solve” the archive by inventing an exhaustive account. The response must be methodological: to bound claims, to treat citation as part of method rather than decoration, and to hold conceptual vocabularies vulnerable to revision. This article therefore makes a limited claim. It is not ethnography, and it does not presume total interpretive access to Daveyton’s everyday visual life. Instead, it works with published scholarship on Daveyton’s historical governance and spatial politics (Nieftagodien, 2013), contemporary township creativity and informality (Booyens, 2025), and township sartorial performance and moral economies (Mnisi & Ngcongo, 2023), as well as adjacent work on reputational visibility (Coulter et al., 2025), to identify where inherited theoretical repertoires strain.

2.2 Approach: conceptual work under infrastructural pressure

The term “image-making” is used here in an expanded fashion-studies sense. It includes photography and video, but also the preparatory and performative labor through which subjects become visible: dress, grooming, posture, gesture, staging in space, and the capture and circulation of these performances through mobile devices and platforms. This matters because township image-making is often misread when treated as a set of images waiting to be interpreted as texts. In many township contexts, the image is also an event-one that produces reputational consequences in peer publics and circulates under uneven access to safety, institutional recognition, and economic stability.

Booyens (2025) argues that contemporary township creativity is frequently overlooked because it does not fit dominant “creative city” narratives and because scholarship is often silent about creative work shaped by informality. That observation has methodological implications for fashion studies: if creativity is emergent in spaces that institutions do not legitimize, then fashion theory must be able to theorize style and visual intelligence outside its habitual institutions. In other words, the question is not only “What does this image mean?” but “What does this image do-socially, reputationally, and materially-under constraint?”

5. Vernacular Formalism as a Problem Term

“Vernacular” has a long colonial afterlife. In cultural discourse, it has often functioned as a classificatory move that renders practices legible to Eurocentric archives while keeping them peripheral-valuable as “local color,” not as concept-producing force. Within this history, naming township formal intelligence as “vernacular” can quietly reproduce an older distribution of authority: the center names; the periphery is named.

For this reason, vernacular formalism is not presented here as a stable analytic category. It is used as a problem term that marks a tension:

1. There is rigorous formal intelligence produced outside institutional authorization.

2. Naming that intelligence risks containment-making it safe, tasteful, and theoretically manageable.

The value of the term, if any, lies in keeping this tension visible. It insists that form-making under constraint can be formally rigorous without awaiting institutional validation; it also insists that the language used to acknowledge such rigor must remain alert to colonial residues. If the term begins to domesticate-if it becomes a label that smooths friction-then it should be abandoned rather than defended.

6. Infrastructural Visibility: A Vocabulary for Ambivalent Appearance

“Infrastructural visibility” is the concept that ties the argument together. It names the fact that in many township contexts, visibility is not simply given; it is made. It is made through material resources (phones, data, access to spaces), social resources (networks, audiences, rivals), and historical constraints (racialized planning legacies, surveillance, moral scrutiny).

Visibility, here, operates like a resource that can be accumulated, converted, and contested-sometimes empowering, sometimes exposing. This is where the historical governance of Daveyton becomes an analytic rather than merely contextual point: if publicness was historically engineered, then appearing remains politically charged (Nieftagodien, 2013).

Infrastructural visibility also reframes the relationship between fashion and image. Dress is not only semiotic content; it is part of a technique of public existence. It is a way of claiming legibility under conditions where institutions can be absent or hostile. This does not mean romanticizing visibility as resistance. It means insisting on ambivalence: the same image can generate esteem and stigma, belonging and exposure.

This ambivalence has methodological consequences. It suggests that fashion studies should not rely on visibility as an uncomplicated good, nor assume that “more representation” is necessarily the goal. It also suggests that a critical account of township image-making must remain attentive to the costs of appearing-economic, social, emotional-and to how quickly visibility can turn into vulnerability.

7. Introducing Working Terms Without “Naming” Township Life

To describe what township image-making in Daveyton brings into view-without treating township practice as raw material awaiting academic naming-I use three working terms as provisional analytic handles.

I call situated realism the way “the real” is often claimed as a form of social legibility and dignity rather than presented as descriptive fidelity, a move that becomes clearer when township sartorial performance is read through moral economies and recognition struggles (Mnisi & Ngcongo, 2023; Coulter et al., 2025).

I use vernacular formalism to signal that formal intelligence can be produced and evaluated through peer publics and informal infrastructures rather than through institutional authorization, a point that resonates with accounts of township creativity emerging beyond dominant creative-city frames (Booyens, 2025). But the term is held as unstable and potentially disposable.

Finally, I use infrastructural visibility to name visibility as a materially and socially conditioned resource-structured by space, governance histories, device-based circulation, and uneven institutional access-rather than as an uncomplicated good (Nieftagodien, 2013).

These terms are intentionally framed as heuristics. They are meant to make the limits of inherited theory discussable within fashion studies, not to replace local vocabularies or to claim ownership over practices that are already theorized-often more sharply-within the worlds that produce them.

8. Implications for Fashion Theory: From Archive to Repository

Decolonial fashion discourse has emphasized that coloniality is constitutive of fashion’s modern operations, shaping archives, curricula, and institutional “common sense” (Cheang et al., 2022; Cheang & Suterwalla, 2020; Jansen, 2020). These interventions have exposed how fashion’s claims to universality are entangled with colonial modernity and with the making of “non-fashion” sacrifice zones (Niessen, 2020), and they have argued for decolonial practice across pedagogy and curation (Cheang & Suterwalla, 2020; De Greef, 2020) as well as for rethinking luxury’s colonial entanglements (Slade, 2020).

Township image-making pushes these arguments further by raising infrastructural questions: what if fashion knowledge is produced primarily in informal publics, outside institutional validation? What if theory has long depended on such sites while refusing them epistemic centrality? In that case, decolonial work cannot remain only a matter of expanding syllabi or diversifying citations. It also requires fashion theory to develop methods that can be accountable to practices that do not sediment into familiar archives.

This shift can be described as moving from the archive to the repository. The archive, in its dominant academic usage, privileges what is already stored, authorized, and retrievable. The repository, by contrast, emphasizes ongoing formation: it is built through relationships, living transmission, and contested publics. Township image-making suggests that fashion theory needs repository-thinking-not in order to romanticize informality, but in order to acknowledge where theory is already being produced and adjudicated outside institutional centers.

Three implications follow.

First, fashion studies should treat dress not only as meaning but as method. Dress becomes a way of negotiating how the body can appear and what it can claim in public. This does not abandon semiotic analysis; it situates it within the material and reputational consequences of appearing.

Second, fashion studies needs a more precise theory of visibility. Visibility is often framed as recognition and empowerment. Infrastructural visibility insists on ambivalence: the same image can bring esteem and stigma, belonging and exposure. This ambivalence is not a complication to be smoothed away; it is a key feature of how fashion functions as a technology of social ordering under constraint.

Third, township image-making complicates the discipline’s reliance on “the fashion system” as its implicit analytic center. There are multiple systems of fashion valuation: institutional ones, and peer publics with their own economies and moral logics. Decolonial fashion studies is strengthened when it takes these informal systems seriously as theory-generating.

9. Conclusion: Allowing Theory to Change

This article has argued that township image-making in Daveyton makes visible recurring limits in how realism, masculinity, and formalism are deployed as traveling concepts in visual theory and fashion studies. Realism falters when it equates truth with descriptive fidelity and cannot recognize stylization as a dignity claim. Masculinity falters when it is treated only as representational content rather than as a visibility regime shaped by coloniality and spatial governance. Formalism falters when it presumes aesthetic autonomy and cannot account for form as infrastructural craft governed by peer publics.

Treating Daveyton as a theoretical site does not mean claiming a complete account of township life. It means recognizing where inherited concepts show strain and allowing that strain to reshape theory. The working terms offered here-situated realism, vernacular formalism, infrastructural visibility-are proposed as provisional tools for fashion studies, intended to keep analysis answerable to infrastructural realities rather than only to institutional archives or familiar interpretive models.

Finally, the argument is inseparable from positionality. If fashion theory is to take decoloniality seriously, it must allow sites like Daveyton to do more than illustrate theory-they must be able to reorganize its concepts, its assumptions about visibility, and its understanding of where fashion knowledge is produced.

References

Booyens, I. (2025). Reframing creativity in the city: On the emergence of contemporary township creativity. Regional Studies, 59(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2025.2495797

Cheang, S., Rabine, L. W., & Sandhu, A. (2022). Decolonizing fashion [studies] as process. International Journal of Fashion Studies, 9(2), 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1386/infs_00070_2

Cheang, S., & Suterwalla, S. (2020). Decolonizing the curriculum? Transformation, emotion and positionality in teaching. Fashion Theory, 24(6). https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2020.1800989

Coulter, R. A., Martin, K. D., & van der Westhuizen, L.-M. (2025). Tournaments of destruction: Consumers battling for visibility. Journal of Consumer Research. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucaf011

De Greef, E. (2020). Curating fashion as decolonial practice: Ndwalane’s Mblaselo and a politics of remembering. Fashion Theory, 24(6), 901–920. https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2020.1800990

Eriksen, K. G. (2022). Decolonial methodology and reflexive wrestles of whiteness. Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology, 13(2), 99–116. https://doi.org/10.7577/rerm.4666

Gani, J. K., & Khan, R. M. (2024). Positionality statements as a function of coloniality: Interrogating reflexive methodologies. International Studies Quarterly, 68(2), sqae038. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqae038

Jansen, M. A. (2020). Fashion and the phantasmagoria of modernity: An introduction to decolonial fashion discourse. Fashion Theory, 24(6), 815–836. https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2020.1802098

Nieftagodien, N. (2013). High apartheid and the erosion of “official” local politics in Daveyton in the 1960s. New Contree, 67, 35–55. https://doi.org/10.4102/nc.v67i0.294

Niessen, S. (2020). Fashion, its sacrifice zone, and sustainability. Fashion Theory, 24(6), 859–877. https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2020.1800984

Mnisi, J. G., & Ngcongo, M. (2023). Looking back to look forward: Re-humanization through conspicuous consumption in four African masculine sartorial subcultures—from diamond field’s dandies to Izikhothane. African Identities, 21(2), 341–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2021.1913094

Ratele, K. (2021). An invitation to decoloniality in work on (African) men and masculinities. Gender, Place & Culture, 28(6), 769–785. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2020.1781794

Slade, T. (2020). Decolonizing luxury fashion in Japan. Fashion Theory, 24(6), 837–857. https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2020.1802101

Zembylas, M. (2025). Rethinking positionality statements in research: From looking back to building solidarity. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 48(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2025.2475762

African Fashion Research Institute. (n.d.). New Patterns workshop Daveyton.

de Greef, E., with King Debs, James, S., Mabitsela, L., & Sogaula, S. (2024). Fashioning border spaces: African decoloniality and digital fashion. In M. R. Spicher, S. E. Bernat, & D. Domoszlai-Lantner (Eds.), Digital fashion: Theory, practice, implications (pp. 223–239). Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

Komape, B. (2023, August 9). Authors capture the history of Daveyton in interesting new book. Benoni City Times (The Citizen).

Mbembe, A. (2002). The power of the archive and its limits. In C. Hamilton, V. Harris, J. Taylor, M. Pickover, G. Reid, & R. Saleh (Eds.), Refiguring the archive. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Taylor, D. (2003). The archive and the repertoire: Performing cultural memory in the Americas. Duke University Press.

Dirk Reynders, PhD, is a lecturer, writer, researcher and cultural critic. His research and expertise focus on visual culture, gender and ethnicity. Reynders’ work offers a renewed and modern perspective on social visual culture, exploring the paradox between realism (representation) and formalism (aestheticism). This theme contributes to a better understanding of the role images play in both functional and expressive resistance within gender and inclusion.

He is currently serving as dean of the Media, Arts & Design faculty at PXL University College. In this role, he oversees the academic and administrative functions of the faculty, ensuring the quality of education and fostering a creative environment for students and staff. His leadership is marked by a commitment to innovation in media, arts, and design education.

Your Questions,

Answered

What we do?

We work at the intersection fashion, language, sociology, and architecture - using design as a tool to understand, shape, and re-imagine how communities live, express themselves, and build meaning to the collective well-being.

What types of community programs do you offer?

Our offerings range from skill-building workshops and support groups to neighborhood improvement projects and cultural events. Each program is designed to address specific community needs and promote collective well-being.

How can I volunteer or get involved?

Simply reach out through our contact form or social channels with your area of interest and availability. We’ll match you with current initiatives and provide any necessary orientation or training.

Do you provide virtual resources for remote participants?

Yes. Many of our seminars, discussion circles, and learning materials are available online, ensuring that geography is never a barrier to participation.

Let’s Stay in Touch

Curious about how our services can support your goals or your community’s needs? Schedule a no-obligation consultation today and discover tailored solutions that make a real difference.